The conclusion of a nonfiction book—or any piece of informational writing—needs to leave readers satisfied. One great way to do this is by linking back to the beginning, as students are taught to do when writing a 5-paragraph essay.

The conclusion of a nonfiction book—or any piece of informational writing—needs to leave readers satisfied. One great way to do this is by linking back to the beginning, as students are taught to do when writing a 5-paragraph essay.

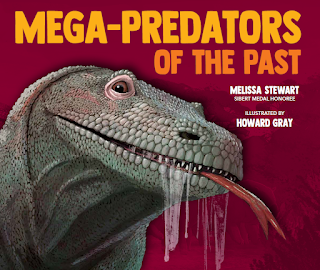

The final spread of Mega-Predators of the Past has two jobs. The text on the left-hand page presents the final animal example—the blue whale. The last sentence creates an important transition by linking to the previous example (the shark Megalodon) and to T. rex, which brings dinosaurs back into the discussion. This paves the path for the text on the right-hand page, which serves as the book’s conclusion.

Like a 5-paragraph essay, the final two-sentence paragraph connects back to the book’s beginning. It reinforces the argument that dinosaurs are “overexposed and overrated” and “other prizeworthy predators of the past,” such as the ones highlighted in this book, deserve more attention.

If this book were being evaluated by the people who grade standardized tests, it would probably lose some points because the ending doesn’t specifically mention that the “other prizeworthy predators” have a lot in common with animals alive today, but I trust my readers. They can infer that “other” refers to all the animals featured throughout the book, and each page featured a graphic that compared the prehistoric creatures to modern animals.

I made this choice because I thought sneaking in that extra bit of information was unnecessary and I worried that it would disrupt the voice and ruin the flow.

This decision highlights an important difference between writing a book I want kids to love and writing an essay for a standardized test. The reader’s experience is more important that checking all the boxes on a rubric.

Nevertheless, anyone analyzing the overall structure of this list book can’t help but notice how similar it is to a 5-paragraph essay. There’s an introduction, a conclusion, and each spread in between presents a specific example that supports the main idea.